Generation X’ers aren’t mini-Boomers. Raised in a rapidly growing economy by parents that approached child rearing as a competitive activity, they saw more, did more, and were given more than their parents could have dreamed of.

I took my first commercial airline ride when I was 25 years old (and before my mother’s first flight). My two sons had each boarded planes over 50 times before they were in high school.

I was not an athlete, and have no hardware to display testifying to any athletic prowess. My youngest son made varsity in one sport, for one year. Yet he has a bookcase full of trophies.

I received a couple of piano lessons from a neighbor who played. My children had paid instructors for martial arts, gymnastics, baseball, piano, viola, singing, and math. They are far from the most-coached kids I know.

The challenge of selling a business to a small and disinclined group of prospective buyers starts with their lack of numbers, but it is just as much about how they were raised by their Boomer parents. Generation X has different values and many more choices.

Values

The numbers are just the most obvious (and the most inevitable) factor impacting Generation X as buyers. The second factor is values. Every Boomer owner I know, and there are hundreds, has complained about the expectations and the lack of a decent work ethic among Generation X. This isn’t caused by a special laziness gene. It is a matter of values.

Boomer “super parents,” driven by their competitive approach to everything, raised children who expected to be accepted for who they are, and to have things done for them. Boomers created the  children’s ball team where everyone got a trophy just for participating, regardless of the team’s success. X’ers watched their parents struggle with a breakneck pace and the concept of work-life balance and, like every generation of offspring, saw their parents’ approach to life as stupid.

children’s ball team where everyone got a trophy just for participating, regardless of the team’s success. X’ers watched their parents struggle with a breakneck pace and the concept of work-life balance and, like every generation of offspring, saw their parents’ approach to life as stupid.

So Generation X, by and large, doesn’t equate material comfort directly with work. Their “balance” is oriented towards separating work and life. Unlike most Boomers, who live to work, the X generation only works to live. Work isn’t their identity, it is merely the thing that permits them to finance what they really want to be.

For Boomer entrepreneurs, who accept a 50 or 60 hour work week as simply part of the cost of business ownership, that isn’t good news. The next generation of buyers doesn’t agree with you, and isn’t interested in subordinating their lives to the quest for success.

Choices

I know five local CPA firms that have sold to regional or national competitors in the last 3 years or so. Each had the same problem. They had built a model where the retirement of the Boomer founders was dependent on the profits to be generated by the next generation of partners. Unfortunately, that generation wasn’t interested in assuming the required work load. In several of the cases, a younger partner was invited to a meeting, where the senior partners announced that he or she had been selected as the next leader of the firm. To their shock, the annointee turned them down flat.

Corporate America is aware of the coming shortage of educated, hard-working, middle-aged executives. They are recruiting them with far greater benefits and perquisites than a small business can afford.

Since the 1970’s, a flood of regulation and increasing liability connected to business ownership makes the entrepreneurial proposition riskier and more tedious. The Boomers have only themselves to thank for that.

The retirement of the Boomers is placing a crushing burden on Medicare, Social Security and pension funds. The likelihood of greater taxation, and lower benefits for those who follow, detracts from the attraction of working hard to make a lot more money.

Finally, technology has vastly expanded Gen X’s choices. Flex time, telecommuting, job sharing, family leave and home-based businesses make the traditional model of sitting in a business all day look far less appealing.

The bleakest future is for a small business that has few factors, other than the owner’s personal reputation, to differentiate it from its competitors. It depends on the ongoing efforts of its owner to produce revenue. It has a number of employees who are only trained on the job, or who possess few distinctive skills that make them an integrated part of the business. It has no incentives that lock the best performers into long term relationships. It lacks middle management, or anyone who can run the business indefinitely without the owner around to make decisions.

If that describes the business you own, it is time to start making changes. The generation that is reaching business-buying age has more choices for earning a living, and many more choices that better fit their values.

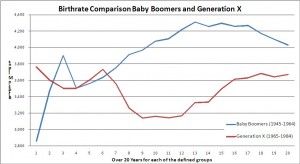

This series is focused on Boomers who are preparing to exit their businesses. For owners who precede the Boomers (currently in their 70’s), there is still a market of younger Boomers (in their late 40s and early 50s) to sell to. We are describing a problem that is only going to accelerate in the next 5 years. It is unavoidable, and the numbers are irrefutable.

There is some good news. You can do something about it. Most small business owners will remain oblivious to the realities of the market until they try to sell, and even then probably won’t understand the reasons why they can’t.

Like the hiker running from the bear, you don’t have to be faster than the bear. You just need to be faster than the other hiker. Simply reading this puts you ahead of the pack. We next turn our attention to what it will take to successfully exit your business in the toughest selling market in history.

(This is the seventh installment in a series about “Beating the Boomer Bust.” Previous installments are The Approaching Tidal Wave, The Pig in the Python, The Brass Ring, Work-Life Balance, Outsourcing America and The X Factor.)

for admission into the better universities; and then competed fiercely for jobs when they graduated. Once employed, they were part of a glut of other qualified Boomers; roughly the same age, and with similar qualifications. The brass ring went to the ones that worked hardest, longest and smartest. An entire generation accepted competition as a way of life. It was a numerical inevitability.

for admission into the better universities; and then competed fiercely for jobs when they graduated. Once employed, they were part of a glut of other qualified Boomers; roughly the same age, and with similar qualifications. The brass ring went to the ones that worked hardest, longest and smartest. An entire generation accepted competition as a way of life. It was a numerical inevitability.