Great employees are a wonderful gift, but individual heroics aren’t healthy for your business.

Someday, you will start thinking about leaving the business. Perhaps you already do. When you begin planning for your transition, what will your company systems sound like when you describe them to a critical buyer?

“Yes, we have a process for that. It hasn’t been updated, but Martha knows it like the back of her hand.”

“We really don’t have anyone cross-trained on that machine. Bucky likes to work alone, but it’s okay because he hasn’t taken a vacation in three years.”

“We always use Andy on that route. There are lots of traffic snarls, and he’s the only one who seems to be able to finish on schedule.”

You are getting the point. When an employee is especially productive or reliable, it’s easy to become dependent on his or her individual heroics. It’s one fewer function of the business that you have to watch.

It is ironic that the very behaviors that make your life easier appear to be threats in the eyes of a prospective buyer. You know that they could pose a problem, but they haven’t so far. Why fiddle with what’s working?

It is ironic that the very behaviors that make your life easier appear to be threats in the eyes of a prospective buyer. You know that they could pose a problem, but they haven’t so far. Why fiddle with what’s working?

The answer is because individual heroics discount the value of your business. A buyer worries that key workers might not like his or her management style. As a new owner, he might be immediately approached for pay increases. Worst of all, if one of your heroes’ performance heads south, he may not be able to fix it, or even know what is happening.

For just a moment, look at your best employees as threats. Do you have a contingency plan for each? Can Martha’s process be documented so anyone can do it? Is Bucky just a loner, or is he trying to make himself irreplaceable? Can Andy’s mental map be duplicated by routing software?

And in case you didn’t realize it, “I can do any of those jobs myself. ” is the worst of all possible answers. Those kind of individual heroics will send the buyer towards the exit instead of you.

Dependable high performers are invaluable, but they are frequently protective of their status. Recognize them, but make it plain that that their work needs to be duplicable. (Although, “Of course, not at the level you perform.”)

If you don’t, start looking at them as liabilities rather than assets.

Do you know a business owner who would enjoy Awake at 2 o’clock? Please share!

Selling to employees requires legal agreements, specialized compensation plans and a willingness to run the company transparently. The return is a team that is committed to the long term, highly motivated, and all on the same page when it comes to growing the business.

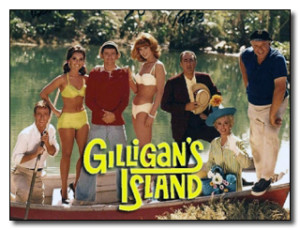

Selling to employees requires legal agreements, specialized compensation plans and a willingness to run the company transparently. The return is a team that is committed to the long term, highly motivated, and all on the same page when it comes to growing the business. Perhaps the most amusing application was in “Gilligan’s Island.” The seven castaways fill their assignments well. There’s Gilligan (Sloth), the Skipper too (Wrath). The millionaire (Thurston Howell — Greed) and his wife (Gluttony). The movie star (Ginger — Lust, of course); The professor (Pride) and Mary Ann (Envy), here on Gilligan’s Isle (Hell?)

Perhaps the most amusing application was in “Gilligan’s Island.” The seven castaways fill their assignments well. There’s Gilligan (Sloth), the Skipper too (Wrath). The millionaire (Thurston Howell — Greed) and his wife (Gluttony). The movie star (Ginger — Lust, of course); The professor (Pride) and Mary Ann (Envy), here on Gilligan’s Isle (Hell?) Pride has characteristics that are easily recognizable in some owners. In meetings, do you do all the talking? Do you complain that you are the only one who has new ideas? Does everyone come to you for the solutions to any and every problem? Worse yet, do you insist on it? Do you reprimand employees for making decisions that, while they might work, aren’t exactly the way you would have done it?

Pride has characteristics that are easily recognizable in some owners. In meetings, do you do all the talking? Do you complain that you are the only one who has new ideas? Does everyone come to you for the solutions to any and every problem? Worse yet, do you insist on it? Do you reprimand employees for making decisions that, while they might work, aren’t exactly the way you would have done it? You are guilty of Envy if you think everyone else has better employees than yours. If you believe that other owners are making more money, or have a better work/life balance than you, envy is a problem. The common envious phrase that I hear is “My problems are different. No one else has a business that’s as difficult as mine.”

You are guilty of Envy if you think everyone else has better employees than yours. If you believe that other owners are making more money, or have a better work/life balance than you, envy is a problem. The common envious phrase that I hear is “My problems are different. No one else has a business that’s as difficult as mine.”