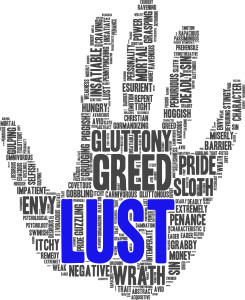

We continue the Seven Deadly Entrepreneurial Sins series that we started here. We’ve covered the two Operational Sins (Lust and Gluttony) that make you less effective as an owner. Sloth is the first of the Tactical sins; those that make your operation less effective. The second is Wrath.

Forget the dictionary definition of Wrath, although depending on how your employees see you, the part about “referring to divine retribution” may be appropriate. <grin> Wrath is, by anyone’s definition, created by a surplus of adrenalin.

Forget the dictionary definition of Wrath, although depending on how your employees see you, the part about “referring to divine retribution” may be appropriate. <grin> Wrath is, by anyone’s definition, created by a surplus of adrenalin.

If you are the founder of your business, adrenalin probably got you through long hours and late nights. It helped take your game to another level when failure wasn’t an option. It still comes in handy when you walk into the business tired or preoccupied, and find that you have to immediately launch into firefighting mode. But Wrath, depending on adrenalin to deal with problems, has no place in a well-run company.

Steven Covey said that the more time you spend in his urgent/important quadrant of task rankings, the less time you have for real CEO activities. Eventually you will only have time for urgent/important, moving from crisis to crisis with barely enough time to catch your breath in between.

When there are delays, or a flood of work that strains capacity, is your standard answer that everyone just has to buckle down and work harder? Do you worry about taking vacation because your employees will slack off without you there to drive them? Are you frustrated by their lack of urgency? Are you a willing listener when employees complain about each other?

Your adrenal glands (you have two) have a species-survival purpose. When faced with a “fight or flight” decision (“Uh oh, big animal, do I try to kill it or is it going to kill me?”), an adrenaline surge increases you heart rate and floods blood to the brain. You think faster, feel stronger, and are less conscious of pain.

This is a business, rather than a medical column, so I’ll go lightly on the effects of Adrenal Fatigue; but it is a real syndrome, and I’ve seen may business owners suffer from it. Just like any other organ, adrenal glands can be pressed to maximum performance for only so long before they start to deteriorate. Once you reach the “burnout” stage of continuous exhaustion, and start having difficulty in making decisions, it usually takes six months or more to recover.

The Business Virtue that counters Wrath is Planning. We aren’t talking about high-level Strategic Planning. While that is advisable, no strategic plan can anticipate the day-to-day issues of running the company. That’s why Wrath is a Tactical Sin.

Any amount of planning will lower your adrenalin abuse. What would happen if your thought was; “I hear a noise around the next turn in the trail. It might be a big animal. If it is a deer, I’ll kill it for dinner. If it is a lion, I’ll run.”

Do you feel the difference in your reaction, even to this hypothetical problem? You are still ready to use your fight-or-flight mechanisms to react, but that little bit of preparation increases your feeling of control, and reduces the adrenaline surge.

I once had a manager who insisted on meeting me in the parking lot each morning with his problem of the day. I told him repeatedly that if he didn’t at least wait until I had a cup of coffee and got into my office, I would fire him. He never could get that. He thought his problem was the most important thing on the planet, and he had to tell me about it as soon as possible. So I fired him.

Planning starts with today. Consider a huddle in the morning with your key people to discuss their plan for the day’s activities. If most of your crises are passed upwards to you, have your direct reports start planning tomorrow’s activities. Once you get them in the habit of planning for a day or two, start them on planning for the next week. Most importantly, don’t fall back on Wrath when they are slow to get it.

I have a client who has built a number of successful locations for his retail business. He recently told me, “I worry that I’ve lost my appetite for risk. Years ago I would drive past a location I liked, and within a few months we’d have a new store there. Now I go through so much research and debate about traffic, demographics, return on improvements and lease negotiations. Have I lost my nerve?”

I pointed out that his increased reliance on planning likely came from some of his experience with the results of not planning. He agreed, and that made him feel better.

Thanks for reading Awake at 2 o’clock? Please share it with other business owners.

Lust is the sin that springs from a lack of self-control. As an owner, few people in your business (if any at all) say no to you. They ask, “Boss, did you do that really important thing you were supposed to do yesterday?” You respond, “No, because something more important came up.”

Lust is the sin that springs from a lack of self-control. As an owner, few people in your business (if any at all) say no to you. They ask, “Boss, did you do that really important thing you were supposed to do yesterday?” You respond, “No, because something more important came up.”