When I was a kid my mother said “Money isn’t everything” in response to every envious glance at another kid’s stuff. As I became successful enough to afford things for my children, I reversed the meaning. “Money isn’t everything” became my reminder that their possessions didn’t make them better or happier than others.

The same holds true for companies. An entrepreneur who is struggling to generate sufficient working capital is an unlikely prospect for a lender, let alone an investor.

I regularly receive approaches from business owners who have a great ideas, but have run out of capital without generating cash flow. They usually have trouble understanding why I don’t want to represent them in their investment search (for a fee contingent on only my success, of course.)

“But everyone says there is plenty of money looking for deals,” they say. It is true. There is always more money available than good investments. That’s why so many investments lose money.

Once your business approaches $1 million in annual earnings, the whole capital landscape changes dramatically. If you are scalable (meaning you likely have around 100 employees or more) your deal is attractive to financial investors such as private equity groups. There are currently about 7,000 such buyers in the US, pursuing the 17,000 or so companies who meet their criteria.

These buyers range from Search Groups (who have investors lined up if they find a company), to investment funds with a billion dollars or more in “dry powder” (cash in the bank).

If you are smart, and clever, and tenacious, and lucky, you can reach the point where there is plenty of money to buy you out. In fact, money is probably chasing you. Most sellers, however, come to realize that money isn’t everything.

The M&A world abounds with horror stories of financial buyers who stripped the employee benefits from a company and drove off its key personnel. Others pulled their capital as soon as they had control (to leverage it in another deal) and left the business staggering under the debt replacing it. Still more inserted a Hired Gun executive from another industry whose inexperience quickly ran the business on the rocks.

The M&A world abounds with horror stories of financial buyers who stripped the employee benefits from a company and drove off its key personnel. Others pulled their capital as soon as they had control (to leverage it in another deal) and left the business staggering under the debt replacing it. Still more inserted a Hired Gun executive from another industry whose inexperience quickly ran the business on the rocks.

That might not be your concern if you walk away with a terrific multiple, but if the deal (like many) requires you to leave a substantial amount on the table for a few years, it’s critical.

I work with business owners in their exit planning. Although I haven’t brokered in years (meaning list and market businesses for sale), I regularly advise owners who are dealing with an approach from financial buyers. Here’s my mental checklist for vetting a financial buyer:

- Do you trust them? Can you see working side by side with them as your partners?

- Do they understand your business and your customers, or are they just looking at your financial statements?

- How important to you is the future of your employees and your reputation?

Notice that the questions don’t include “How much money do they have?” If you are attractive to one financial buyer, you are probably attractive to a lot more.

Many of my clients, when they examine the non-financial aspects of selling, choose alternative exits. They arrange for the employees to buy the business, or merge with a friendly competitor. They may not make quite as much, but money isn’t everything.

If you enjoy Awake at 2 o’clock and know a business owner who would benefit from reading it, please share. Thanks!

Selling to employees requires legal agreements, specialized compensation plans and a willingness to run the company transparently. The return is a team that is committed to the long term, highly motivated, and all on the same page when it comes to growing the business.

Selling to employees requires legal agreements, specialized compensation plans and a willingness to run the company transparently. The return is a team that is committed to the long term, highly motivated, and all on the same page when it comes to growing the business. First, there is the question of who is covered by the agreement. Most allow for advisors to each party to see the agreement. That can encompass accountants, attorneys, consultants, bankers and employees. I think employees present the greatest risk, since they are the most likely to personally benefit from information about customers, vendors and pricing.

First, there is the question of who is covered by the agreement. Most allow for advisors to each party to see the agreement. That can encompass accountants, attorneys, consultants, bankers and employees. I think employees present the greatest risk, since they are the most likely to personally benefit from information about customers, vendors and pricing. Bob is calculating what the brokerage industry calls “Seller’s Discretionary Benefits” or SDE. While it is a legitimate way to look at the full value of business ownership, ball park valuations of 4-5 times pre-tax earnings don’t apply to that calculation. Cash flow expensed for benefits (rather than dropping to a taxable bottom line), isn’t included in those earnings multiples. The traditional multiple for a small business sale averages 2.5 time SDE, or half of what Bob is estimating. We are immediately reducing the likely price to something like $1,250,000.

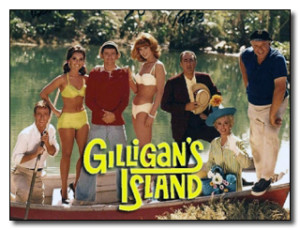

Bob is calculating what the brokerage industry calls “Seller’s Discretionary Benefits” or SDE. While it is a legitimate way to look at the full value of business ownership, ball park valuations of 4-5 times pre-tax earnings don’t apply to that calculation. Cash flow expensed for benefits (rather than dropping to a taxable bottom line), isn’t included in those earnings multiples. The traditional multiple for a small business sale averages 2.5 time SDE, or half of what Bob is estimating. We are immediately reducing the likely price to something like $1,250,000. Perhaps the most amusing application was in “Gilligan’s Island.” The seven castaways fill their assignments well. There’s Gilligan (Sloth), the Skipper too (Wrath). The millionaire (Thurston Howell — Greed) and his wife (Gluttony). The movie star (Ginger — Lust, of course); The professor (Pride) and Mary Ann (Envy), here on Gilligan’s Isle (Hell?)

Perhaps the most amusing application was in “Gilligan’s Island.” The seven castaways fill their assignments well. There’s Gilligan (Sloth), the Skipper too (Wrath). The millionaire (Thurston Howell — Greed) and his wife (Gluttony). The movie star (Ginger — Lust, of course); The professor (Pride) and Mary Ann (Envy), here on Gilligan’s Isle (Hell?)