Many owners want to see their children inherit the business, but what happens when the kids don’t cut it?

Some years ago I worked with a business owner whose exit plan was to sell into one of the private equity roll-ups that were active in his industry. His son was finishing college, where he studied for a career in wildlife management. The son’s ambition was to spend his life in the great outdoors.

One day my client was beaming when I walked into his office. “Guess what?” he said. “My son called. He wants to take over my business!” After a few minutes, it was pretty clear that we weren’t going to have a conversation about experience or qualifications. This owner had a whole new exit plan.

Fortunately, that plan worked out. There was strong management in place, and the son paid his dues in sales and management training before the transition. Not all such shifts work out that way.

When kids don’t cut it

There was another prospect who gave me my “assignment” for proposing. “My son has been in the business for the last ten years. He seldom shows up. He is nominally in charge of a department, but we do little or no business in that area. He’s abusive when he is here, and all the employees hate him.”

There was another prospect who gave me my “assignment” for proposing. “My son has been in the business for the last ten years. He seldom shows up. He is nominally in charge of a department, but we do little or no business in that area. He’s abusive when he is here, and all the employees hate him.”

“We (his mother and I) want to sell him the business, and we need him to perform well to fund our retirement. How much will you charge to straighten him out and get him to run the business right so he can pay us?”

I wanted to answer “Infinity,” but chose instead to politely decline the engagement.

I’ve written many times about the attachment a founder has for his or her business. Of course, parents (hopefully) have an even stronger bond with their children. Watching the first client’s face light up when he made the announcement was the best illustration of how important legacy preservation can be to an owner.

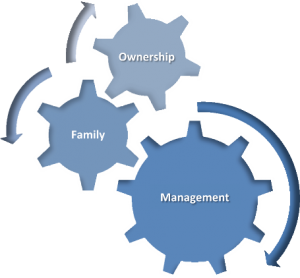

Yet, keeping the business in the family isn’t always the best idea. It involves a number of stakeholders, including employees and other children.

Key Employee Issues

For brevity, we will start by presuming that you’ve never promised, indicated, discussed, or even hinted to key employees that they were going to own the company. If you have, that’s a whole different can of worms that we’ll deal with another time.

We also aren’t talking about a succession plan where the son or daughter has always been the heir apparent, and has trained for the position.

Commonly, it’s somewhere in between. The child holds a job in the company, but not the second-in-command position. He or she does it well enough, but isn’t a star. They are interested in ownership (another too-often ignored question,) but their ability to act as CEO in the foreseeable future is doubtful.

Even if key managers aren’t resentful, they are not chattels. Giving ownership to a child is a clear message that their career path has reached a stopping point. It may be an eye-opener, and almost certainly disposes them to look at other opportunities, even if they don’t do so actively. Remember, their loyalty is to you. It isn’t automatically transferrable.

One solution that’s often employed is the perpetuation of the founder/owner. He stays on in a consulting role long after normal retirement age. Often it works out, and it can lend tremendous experience to the company.

If you don’t want to stick around in the “answer man” role, however, you need to secure the continued commitment of the key managers. That should be done through conditional compensation, tied to the continued success of the company. If appropriate, it may also require reaching benchmarks for training the offspring to take the reins of the business.

Long-term compensation can be through virtual equity (Phantom Stock or Stock Appreciation Rights,) direct profit participation, actual minority equity ownership, or supplemental retirement insurance. It needs to be more than just a salary, though. Someone else can always beat a salary.

Keep Thanksgiving Friendly

The other stakeholders who should be considered are the siblings who don’t work in the business. Often the owner wants to leave the business to the child who has worked in it. The owner’s spouse wants to divide it equally among all the children. Both ways are fraught with issues.

Leaving the entire income-producing capability of the family (the company) to one child can obviously create resentment. On the other hand, forcing that child into a lifetime of working for the benefit of his or her siblings is likely to end family Thanksgivings. No one wants to grow a business only to see a third, or half or three-quarters of the benefit go to bystanders.

Some owners choose to balance their estate with other assets outside the business. If that isn’t practical, we frequently recommend dividing the business equally, but with a valuation formula and documented agreement to sell the inherited shares to the active child or children. Everyone benefits from the parent’s work, but going forward the active child keeps any increase in profits (and also bears the risk of any decline.)

Passing the legacy of a successful enterprise to children can be one of the greatest thrills of a parent’s life. When the kids don’t cut it, however, it is wise to face facts and plan accordingly. Glossing over the issues will inevitably lead to more pain down the road.

John F. Dini, CExP, CEPA is an exit planning coach and the President of MPN Incorporated in San Antonio Texas. He is the author of Your Exit Map: Navigating the Boomer Bust, and two other books on business ownership. If you want to see how prepared you are for transition, take the 15-minute Assessment at MPNInc.com/ExitMap.