If you are preparing to sell your business, your buyers will likely be members of the “buy now, pay later” generation. Generation X is the first demographic group to be raised in a culture that put little emphasis on savings.

Diner’s Club was introduced as the first “charge card” in 1960. By the end of that decade competition from member cards (American Express and Carte Blanche) and bank-owned revolving finance cards (MasterCard and Visa) began placing millions of cards in consumers’ hands.

In a competitive credit environment, advertising for the revolving charge cards was directed to the pleasures of paying for something after you already enjoyed the use of it. The struggle of saving for a long time before purchasing was portrayed as foolish and unnecessary. In the 1980s and ’90s Baby Boomers on the quest for material success embraced the concept wholeheartedly.

In a competitive credit environment, advertising for the revolving charge cards was directed to the pleasures of paying for something after you already enjoyed the use of it. The struggle of saving for a long time before purchasing was portrayed as foolish and unnecessary. In the 1980s and ’90s Baby Boomers on the quest for material success embraced the concept wholeheartedly.

This is the environment that today’s prime business buyers between the ages of 35 and 50 grew up in. Americans reached the height of “buy now, pay later” just after the turn of the century. In the early 2000s, when Generation Xers were between 28 and 45 (the prime consumption age range) Americans spent about 2% more than they earned annually.

That was a great formula for boosting an economy, but a lousy way to amass capital for investment. That credit-fueled boom died a gruesome death in 2008, and many debt-laden Xers haven’t yet recovered.

These are the buyers for your business. Many have grown up believing that personal financial management consists of parsing a paycheck to allow enough for food after their installment payments. The US savings rate has since recovered to a more normal 5%; much of it fueled by Boomers belatedly preparing for retirement.

If you’ve spent the last 30 years or more building a business worth a million dollars, you need to find one of these folks who has put aside at least $300,000 or so to buy it outright (a down payment to qualify for financing plus initial working capital.) There are such buyers, including escapees from corporate life with substantial retirement plans and those who will be inheriting their parents’ savings.

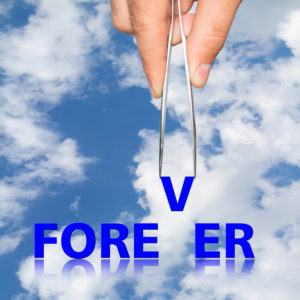

Most buyers, however, don’t have that kind of money. If you want to realize full value for your business, you may want to think about how to accommodate a “buy now, pay later” approach. A buyer who writes a check is more appealing, but good business logic seldom results in complete dependence on a long-shot strategy.

There are four ways to sell a successful business to folks who have no money. The more time you have to implement a plan, the better its chances of success. In order of my preference they are:

- Best – Sell to Employees. A five to ten year period is usually sufficient to get a “down payment” (25-35%) into employees’ hands via stock incentives. The best scenario is earning the awards by growing the value of the business. In a strong company, the owner can leave with the full proceeds in his or her pocket, and remain in control until retirement.

- Better – Hire Your Buyer. This is similar to a sale to employees, but you use the equity plan to recruit a more highly qualified individual than you could otherwise attract. It is better in the sense that the buyer may be stronger, but the time up front to make sure he/she is a good fit represents a risk.

- Good – Finance the Down Payment. For many lenders, including the SBA, stock sold via a subordinated note can qualify as a down payment. It means you walk away with 65-75% of your money, and leave the rest in the business until the first-position lender is comfortable with the stability of their risk.

- Worst – Finance the Purchase. This is often the scenario for an owner who waits too long to consider the options. Whether the buyer is an employee or a third-party, you sell the company for a promissory note and hope for the best.

You have options, but they disappear one by one as you get closer to your exit. That’s why we encourage planning. Having a plan in place doesn’t require immediate implementation, but it does help when evaluating opportunities.

For more on Boomers and Buyers, you can download my free eBook Beating the Boomer Bust.

Following my own advice, I am leaving on my biannual sabbatical. Awake at 2 o’clock will resume on November 6th. In the meantime, please share it with another business owner. Thank you.

It is ironic that the very behaviors that make your life easier appear to be threats in the eyes of a prospective buyer. You know that they could pose a problem, but they haven’t so far. Why fiddle with what’s working?

It is ironic that the very behaviors that make your life easier appear to be threats in the eyes of a prospective buyer. You know that they could pose a problem, but they haven’t so far. Why fiddle with what’s working? But the good customer keeps buying more. They are twenty times your size, and an increase of 2% for them translates into 40% more for you. Businesses in this situation aren’t necessarily complacent. They are just scrambling to keep up.

But the good customer keeps buying more. They are twenty times your size, and an increase of 2% for them translates into 40% more for you. Businesses in this situation aren’t necessarily complacent. They are just scrambling to keep up. For many, the business is a part of them. Shutting it down would be like having a piece of you die.

For many, the business is a part of them. Shutting it down would be like having a piece of you die. The M&A world abounds with horror stories of financial buyers who stripped the employee benefits from a company and drove off its key personnel. Others pulled their capital as soon as they had control (to leverage it in another deal) and left the business staggering under the debt replacing it. Still more inserted a Hired Gun executive from another industry whose inexperience quickly ran the business on the rocks.

The M&A world abounds with horror stories of financial buyers who stripped the employee benefits from a company and drove off its key personnel. Others pulled their capital as soon as they had control (to leverage it in another deal) and left the business staggering under the debt replacing it. Still more inserted a Hired Gun executive from another industry whose inexperience quickly ran the business on the rocks.