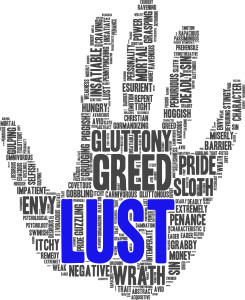

This week we begin discussing the tactical sins. They are those habits of a business owner that impact day-to-day operations; Sloth, Wrath and Greed. To read this series from the beginning, start here.

Few business owners would acknowledge that they suffer from Sloth. Most work very hard. To paraphrase an old New Yorker cartoon, “The thing I like best about self-employment is that I can make my own hours. I’ve chosen to work 24 hours a day.” (Also, see Lust.)

Sloth in your business isn’t a disinclination to put in the effort. It’s the sin of settling for “good enough.”

Sloth in your business isn’t a disinclination to put in the effort. It’s the sin of settling for “good enough.”

If your sales are flat, margins are shrinking or you never experience employee turnover, you may be suffering from Sloth. If you accept financial reporting that is late (after the 15th of the following month), or worry that you wouldn’t know what to do if a major customer defected to a competitor, you are definitely guilty.

There are things you say to your employees that indicate Sloth. Listen for these clues:

- “I know the order isn’t complete, but we are late already. Ship what we have.”

- “Yes, that’s Bob’s responsibility, but I’d rather you handled it.”

- “The bank wants to see our financials. When should I say they’ll be ready?”

- “I think we are making a good profit. We are paying the bills.”

Managing your business isn’t a matter of finding the lowest common denominator. Just because you aren’t going broke doesn’t mean you are running a great company.

The “Business Virtue” that counters Sloth is Benchmarking; the ability to measure your results against a standard. Various management approaches extol Balanced Scorecards, and Key Performance Indicators. “Manage what you measure” is an axiom that is frequently quoted, but far less applied in day-to-day operations.

Benchmarking your company requires that you know how others in your industry or market fare. It doesn’t require industrial espionage. Trade associations, banks and accounting firms have statistical reports with financial metrics by industrial code and company size, most of which they will share on request. Knowing where you stand against other who run businesses like yours is a first step in knowing whether you are doing well, or just surviving.

At the very least, know where your company stands against itself. I’m surprised by how many business owners can’t tell me how their ratios look compared to last year, or the direction of their margin and expense trends.

Internally, Benchmarking requires that you set measurable standards of employee performance. Are your expectations made clear via goals and objectives with concrete deadlines? Is advancement tied to achieving these, or do raises and promotions come because someone is good enough? When was the last time you terminated someone for not improving?

I knew an owner who reviewed a lower-level employee. The worker had a specific job that only he did. He had production goals, which were met in the previous year and qualified him for a raise. The owner congratulated him, and then said “Let’s look at what could be better, so we will know whether you have earned your next salary increase.”

The employee exclaimed “You people are never happy. I quit!” and walked out. He spoke the truth, but the business was in the top 1% of profitability in its industry. They didn’t get there overnight. It took many years of looking for (and measuring) what could be better. Their quest for improvement would not be abandoned for an employee who felt that he was already “good enough.”

Sloth isn’t laziness. It’s the insidious creep that begins when an owner has too much on his or her plate, and lets slide the things that aren’t an immediate problem. Left too long, it may be the most difficult sin to root out of a company’s culture. That’s why we first discussed the sins that affect an owner’s personal performance, Lust and Gluttony. Only after you have tuned up your own efficiency can you begin to work on the issues surrounding you.

I hope you enjoy Awake at 2 o’clock? Please share it with other business owners.

The glutton entrepreneur takes pride in being able to do every job in the company better than anyone else. His or her answer to problems and delays is “Never mind, I’ll just do it myself.”

The glutton entrepreneur takes pride in being able to do every job in the company better than anyone else. His or her answer to problems and delays is “Never mind, I’ll just do it myself.” Lust is the sin that springs from a lack of self-control. As an owner, few people in your business (if any at all) say no to you. They ask, “Boss, did you do that really important thing you were supposed to do yesterday?” You respond, “No, because something more important came up.”

Lust is the sin that springs from a lack of self-control. As an owner, few people in your business (if any at all) say no to you. They ask, “Boss, did you do that really important thing you were supposed to do yesterday?” You respond, “No, because something more important came up.”