A few months ago a business owner asked me to evaluate an acquisition offer for his small business. It was from a larger company headquartered in a different region of the country. They had a branch operation in his city, and wanted to expand their presence by combining it with his.

For an opening offer, the deal seemed very reasonable to me. The purchase price was about four times EBITDA, with half in cash and half with interest over the next three years, and without any conditions attached. (note: That doesn’t mean conditions wouldn’t have come later.) He would receive a three-year employment agreement at a higher salary than he currently paid himself, with additional bonuses for growing the business plus all the benefits he currently enjoyed.

He was unhappy with my assessment, and announced his intention to counter-offer for double the proposed purchase price, with a perpetual employment agreement that would allow him to work for as long as he chose.

While any opening offer is subject to negotiation, I expressed my doubts about attaining a public-company or strategic-level multiple, especially when accompanied by an employment agreement that would make any labor attorney flip out. I asked him how he planned to justify his asking price.

“It just isn’t enough to retire,” he said. “I’d have to keep working indefinitely, and I don’t want to have to go find another job if this doesn’t pan out.”

“It just isn’t enough to retire,” he said. “I’d have to keep working indefinitely, and I don’t want to have to go find another job if this doesn’t pan out.”

Please understand; presenting this story in the abbreviated way that I have makes this owner sound like he is clueless or ignorant. Neither is the case. He has run this business for years, and built it to several times the revenue and profitability of when he acquired it. He has sacrificed personally, putting in long hours and scrimping financially to reinvest in his company. He qualifies as a successful small business owner by most measurements of small business success.

But as a mid-generation Boomer (late 50s) he is coming to the realization that it may not be enough. Like many others, he decided that investing in his own business was more controllable and would produce a higher return than the vagaries of stock markets and mutual funds. His business is his retirement account, and like hundreds of thousands of others, he eventually came to believe his own claim. He expected his company to fund his retirement, without really looking at its objective value in the marketplace.

I asked him if doubling the price would achieve his retirement goal. He thought for a moment, and said “I don’t know, but I doubt it.”

There are roughly 5,500,000 Baby Boomer business owners entering, or already well into, their retirement windows. (The oldest Boomers turn 70 this year.) Many have the expectation that their company is their retirement plan, but there is no assurance that it’s true. If you are over 50 years old, I strongly recommend that you do three things:

- Download and read my eBook “Beating the Boomer Bust.” It’s a collection of ten blog posts from this site with an overview of the challenges that are inevitable with the wave of retiring Boomer exits.. It’s short (45 pages) and its free.

- Get an objective valuation for your business. You don’t need a full appraisal. An opinion of value can range from free to a few thousand dollars, but it shouldn’t cost more than that. (You pretty much get what you pay for, though.) It is critical to understand where you are today.

- Get a realistic projection for how much you will need to maintain your target lifestyle in retirement. A Certified Financial Planner (CFP®) has the training and software to include inflation and tax assumptions. Again, many insurance agents and stockbrokers will provide this for free, but I prefer someone who does it without offering products for sale based on the result.

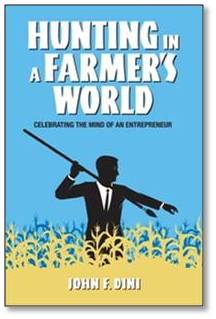

Disclosure: I offer exit consulting for business owners, but I do not provide valuation services, financial planning, wealth management, tax guidance or insurance. I’m just trying to have fewer conversations like the one above. Additional information, including a free, online self-assessment of your business, is at http://exitmap.com.

A Note to My Readers

This January marks the start of my seventh full year of writing Awake at 2 o’clock on a weekly basis. I got serious with the publishing of “The Strategic Triple Threat” in January of 2009, which will probably stand forever as my most accurate piece of economic prognostication. ![]()

Many thanks to the hundreds of you who have commented, and who come up to me at speaking events and say “I’ve been reading your blog for years.” If you read regularly and find yourself nodding in agreement or quoting a column, then I feel that I’m doing my job.

It’s a big, wide Internet out there. Like any blogger, I’m thrilled that I touch so many people with helpful information, but would always like to reach more. Please help by taking a few minutes to pass along a link to any business owners or advisors that you think might also enjoy an owner’s point of view.

Thank you

If you would like a printable pdf of this column or any other, please let me know at jdini@mpninc.com.

for admission into the better universities; and then competed fiercely for jobs when they graduated. Once employed, they were part of a glut of other qualified Boomers; roughly the same age, and with similar qualifications. The brass ring went to the ones that worked hardest, longest and smartest. An entire generation accepted competition as a way of life. It was a numerical inevitability.

for admission into the better universities; and then competed fiercely for jobs when they graduated. Once employed, they were part of a glut of other qualified Boomers; roughly the same age, and with similar qualifications. The brass ring went to the ones that worked hardest, longest and smartest. An entire generation accepted competition as a way of life. It was a numerical inevitability.