As a business owner, planning the exit from ownership of your business is probably the single most important decision you will make. When to exit, how much to walk away with, who to sell it to, what’s the most tax efficient strategy in your circumstance, what timeline is most suitable, and what are the areas of business that need to be improved upon to make it marketable, etc.? Those are just some of the things that need to be considered.

The challenge for many business owners is they don’t want to think about it until they’re absolutely ready to exit. The problem with that is, you won’t know when that will be, and it may happen unexpectedly, due to health and so forth. Furthermore, and especially with “baby boomer” owners, their business is everything to them – They don’t want to think about letting go, so they put it off. Plus, even if they do sell, what are they going to do when running their business isn’t with them every day. – What’s going to be their purpose when that comes to an end? So, they put it off, and when they decide to exit, the business may be unprepared to sell, the market may not be favorable, or they won’t get the price that they thought they would.

All of what I just mentioned, can be addressed or avoided with the proper business exit plan. A proper business exit plan should be done by applying an organized process. It is also important to remember that building a solid exit plan takes time. It’s nothing that you simply flip a switch, and presto, you have a solid exit plan. There are many things to consider, advisors you need to bring in the mix, data that needs to be collected, and analysis that needs to be performed.

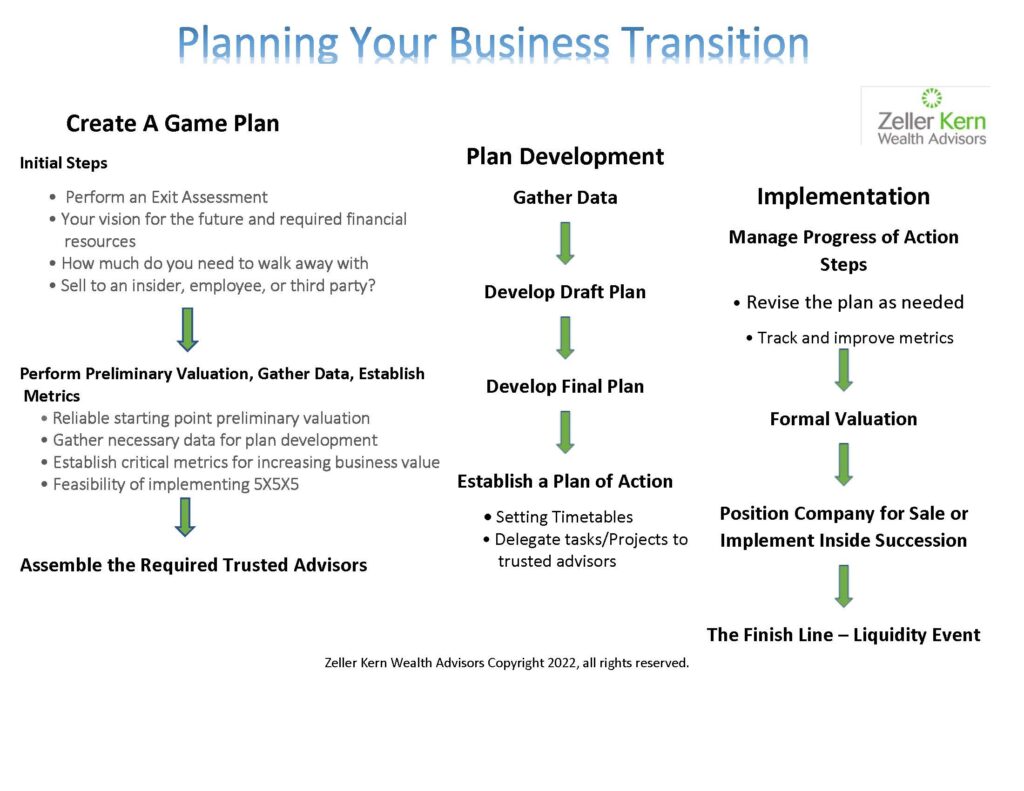

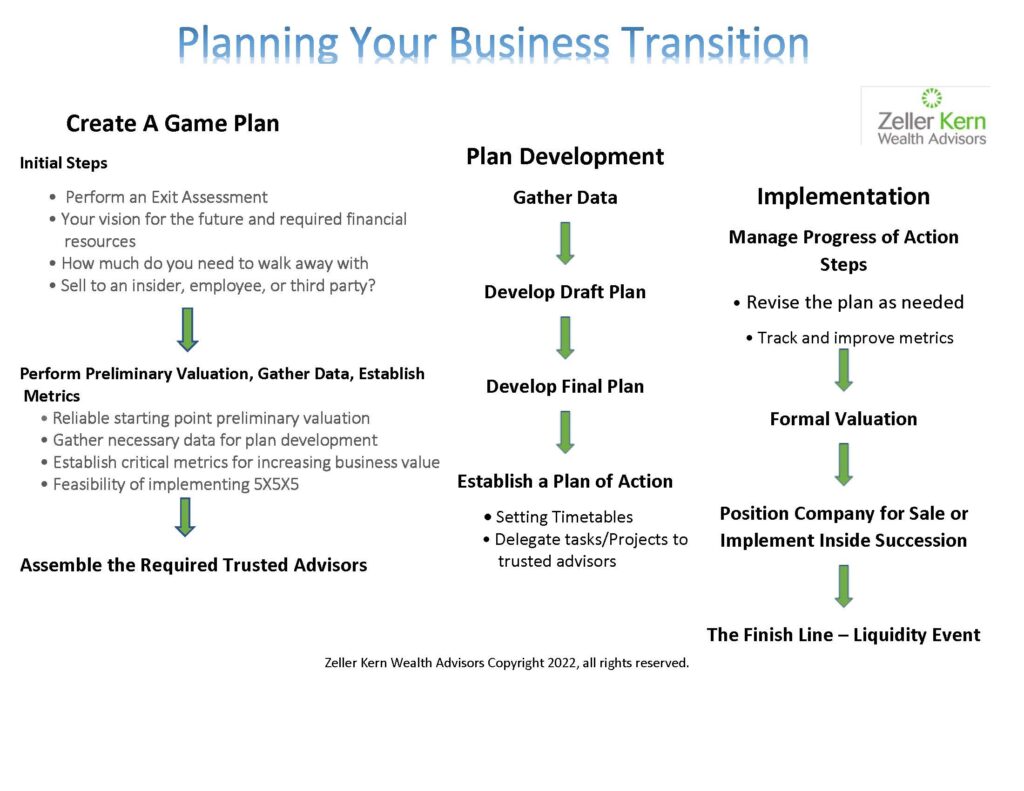

Over the years in consulting my business owner clients, I have developed a “business exit planning process.” The diagram below is an illustration of that process. It breaks the process into three separate phases: “Create A Game Plan”, “Plan Development”, and “Implementation.”

The “Create a Game Plan” phase is the initial phase of the exit planning process. This includes completing an exit plan assessment, which determines what areas you will need to address in order of priority, determining your vision for the future (after you have exited), how much you will need to walk away with, whether to sell to a third party or an insider, performing a preliminary valuation, and assembling your team of advisors.

The “Create a Game Plan” phase is the initial phase of the exit planning process. This includes completing an exit plan assessment, which determines what areas you will need to address in order of priority, determining your vision for the future (after you have exited), how much you will need to walk away with, whether to sell to a third party or an insider, performing a preliminary valuation, and assembling your team of advisors.

For performing an exit plan assessment, I use a tool called “ExitMap”, which is a handy tool and takes the client 15 to 20 minutes to complete. Determining your vision for your future, is a discussion of the owner’s life after the business. That is an important discussion and may be a transition that needs to be planned for over a period of time. “Letting go” doesn’t come easy for some business owners. In fact, there are even tests now that can help determine how you will handle it when that time comes, and what to do about it. There is a consultant firm in Southern California, by the name of “Orange Kiwi” that specializes in that type of consulting. Determining how much you need to “walk away with”, involves analyzing how much you will need to live your life after the business and the goals you want to accomplish that require financial resources, and how much you have accumulated outside of the business. This will determine the dollar amount that you will need to walk away with, from the business. This is then compared to the preliminary valuation which reveals the “gap”. For instance, if you need to walk away with $3 – $5 million net after expenses and taxes, and your business is currently worth approximately $2 million, then the “gap” is $1 million to $3 million.

This leads us to performing a “preliminary valuation”, which is an informal valuation and costs a fraction of a formal valuation. It is a necessary step in order to determine where you stand and how much of a financial gap exists. Finally, the last step in this phase, is forming your team of advisors. Exit planning is a team sport, and you need the right people/advisors on your team – Professionals who are experienced and who are willing to work together. The diagram below shows a number of potential advisors, an owner may need a few of them or many of them at different times.

The “Plan Development” phase includes the gathering of data, the development of a draft plan, the development of a final draft plan, and establishing a plan of action which includes setting time tables, delegating tasks to advisors, and so forth. When we gather data, there are many areas to gather from. This includes the financials, performing a 5-year cash flow analysis, a 5-year cash flow projection and a host of other metrics, client base analysis, re- occurring income, etc. The draft plan is a starting point of a plan. It is reviewed by all of the participating advisors, which may include the C.P.A., the business broker or investment banker, the out-sourced C.F.O., estate planning attorney, tax attorney or business attorney, and so on. Depending on your particular situation, some or many of these advisors may be included.

The “Implementation phase” of the planning process includes “managing the action steps”, and revising the plan as needed, performing a formal business valuation (one that holds up in the negotiation of the sale), positioning the company for sale or inside transition, and the liquidity event, or the actual sale.

Managing the action steps is critical, because plan execution is critical. It’s one thing to develop a plan, but implementing it properly is crucial in a successful outcome. The exit planning professional can help an owner with that, so that he or she does not get consumed by it and can continue to work on the business. Performing a final valuation is required, which is a solid valuation to include in the sale of the company and also for tax purposes. Positioning the company for sale is where a business broker or a merger & acquisition professional comes in. They are the ones who will position the company for sale, put the company to market, and help to finalize a sale. It’s better if they are included earlier on.

It is also where the implementation of structuring the company ownership comes in. Meaning, what is the best way to position the ownership of the company to achieve the most tax efficient transaction. For instance, utilizing special trusts that avoid state taxes upon the sale of the company. But, that is for a future discussion.

Then comes the liquidity event or the actual sale of the business. It often doesn’t come easy and negotiating with a third party can be grueling and time consuming. But the better you have planned and prepared, the better the outcomes will most likely be.

My intention of this article is to point out a few things: One, the best way to develop an exit plan is by applying a process. Two, exit planning takes time. Three, exit planning is a team sport and requires the careful selection of advisors. And four, exit planning is a serious subject and requires a thorough discussion – more than a discussion with your local C.P.A., although a C.P.A. is a critical advisor in the exit planning process.

Steven Zeller is a Certified Business Exit Planner, Certified Financial Planner, Accredited Investment Fiduciary, and Co-Founder and President of Zeller Kern Wealth Advisors. He advises business owners with developing exit plans, increasing business value, employee retention, executive bonus plans, etc. He can be reached at szeller@zellerkern.com